Text written by Johanna Thorell in conjunction with the show Phantasmatic Graft at Kunst- und Kulturstiftung Opelvillen Rüsselsheim, 2021

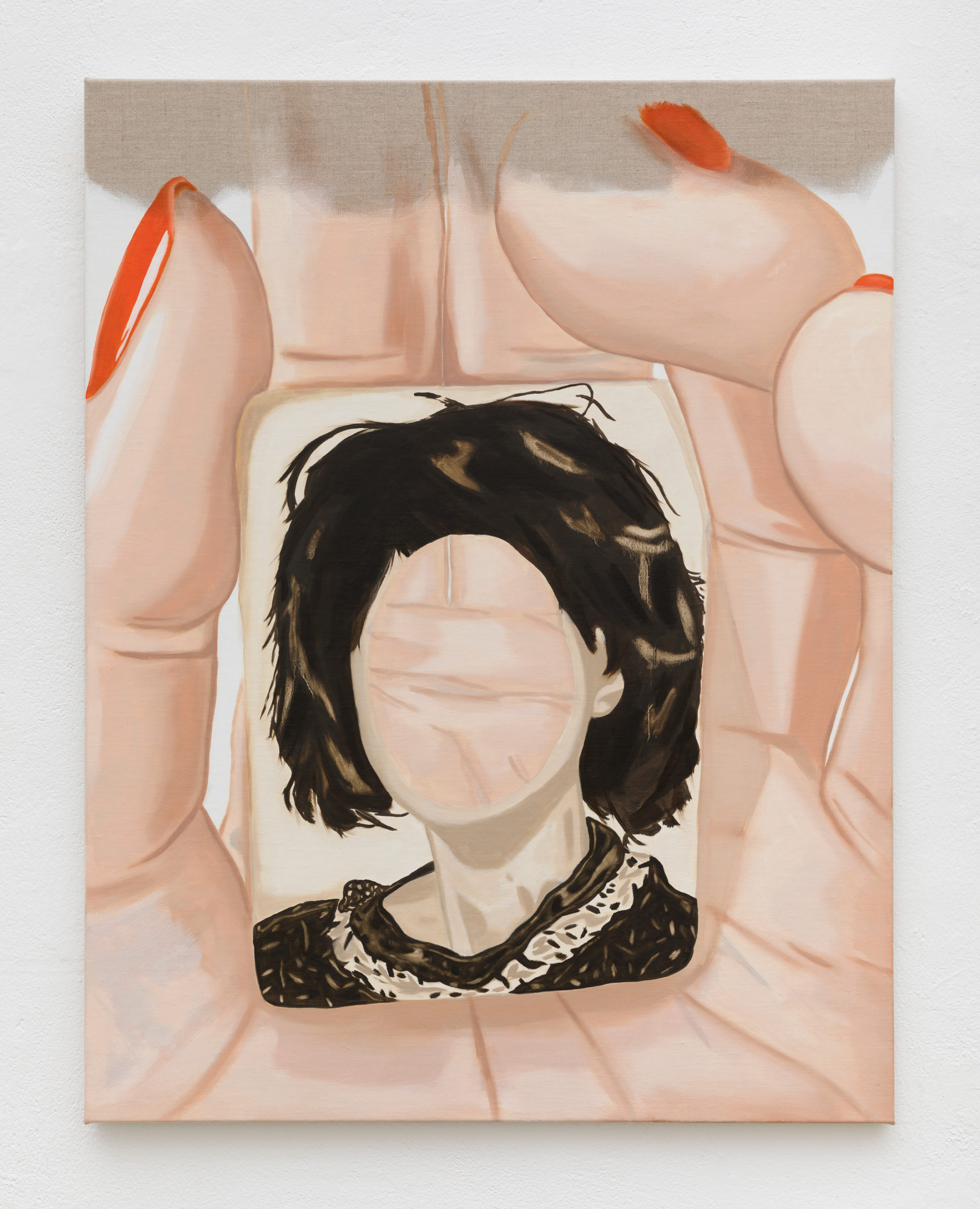

Using oneself as an object of study or the subject matter for a painting may have its obvious reasons, for what could be more at hand than one’s own body? Our body is always here, as the point in the world from which we perceive, move, act, speak, and desire. An inevitable image, it imposes itself upon us every time we face a reflecting surface, yet we can never fully grasp our bodily self. Its many blind spots constantly escape us.

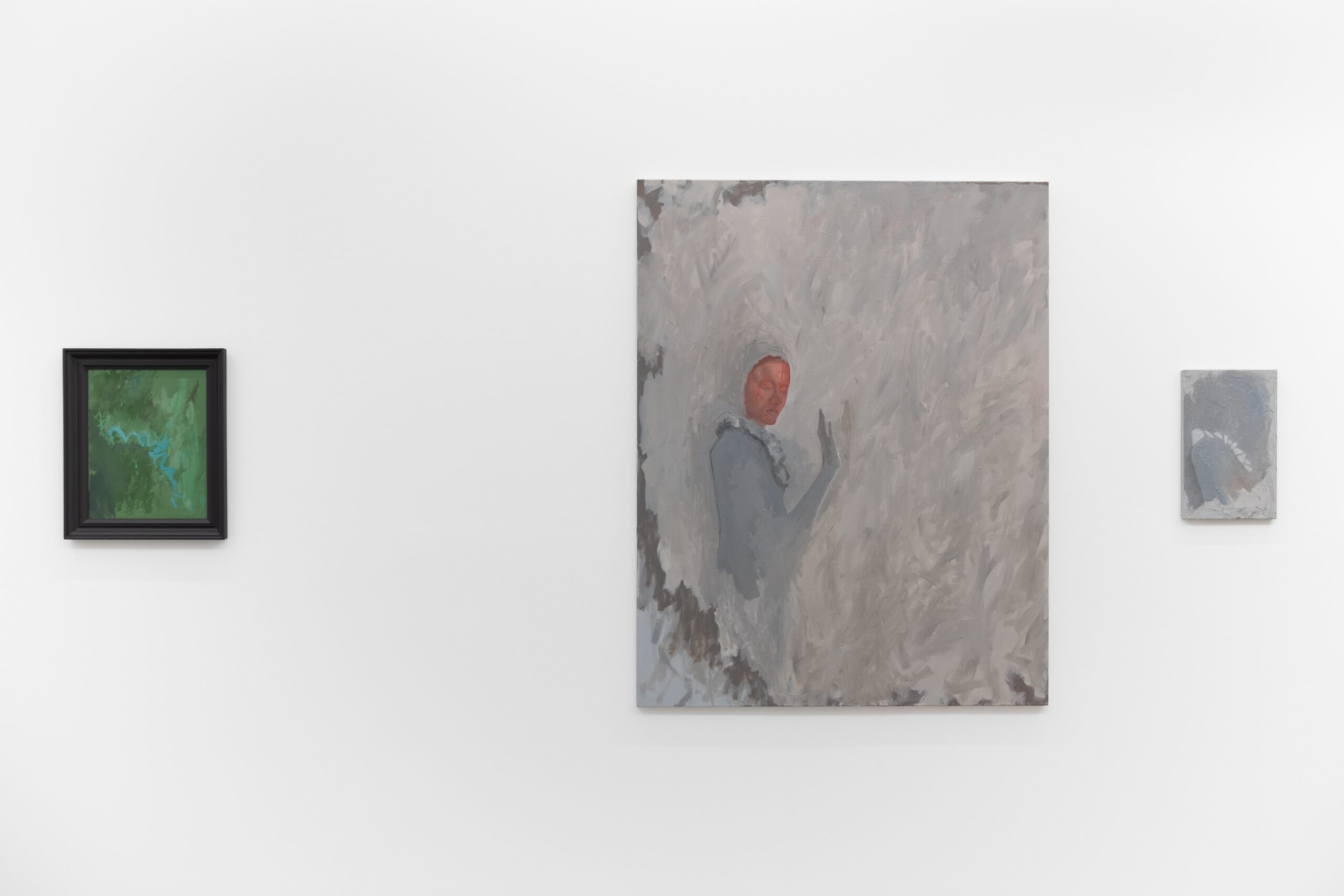

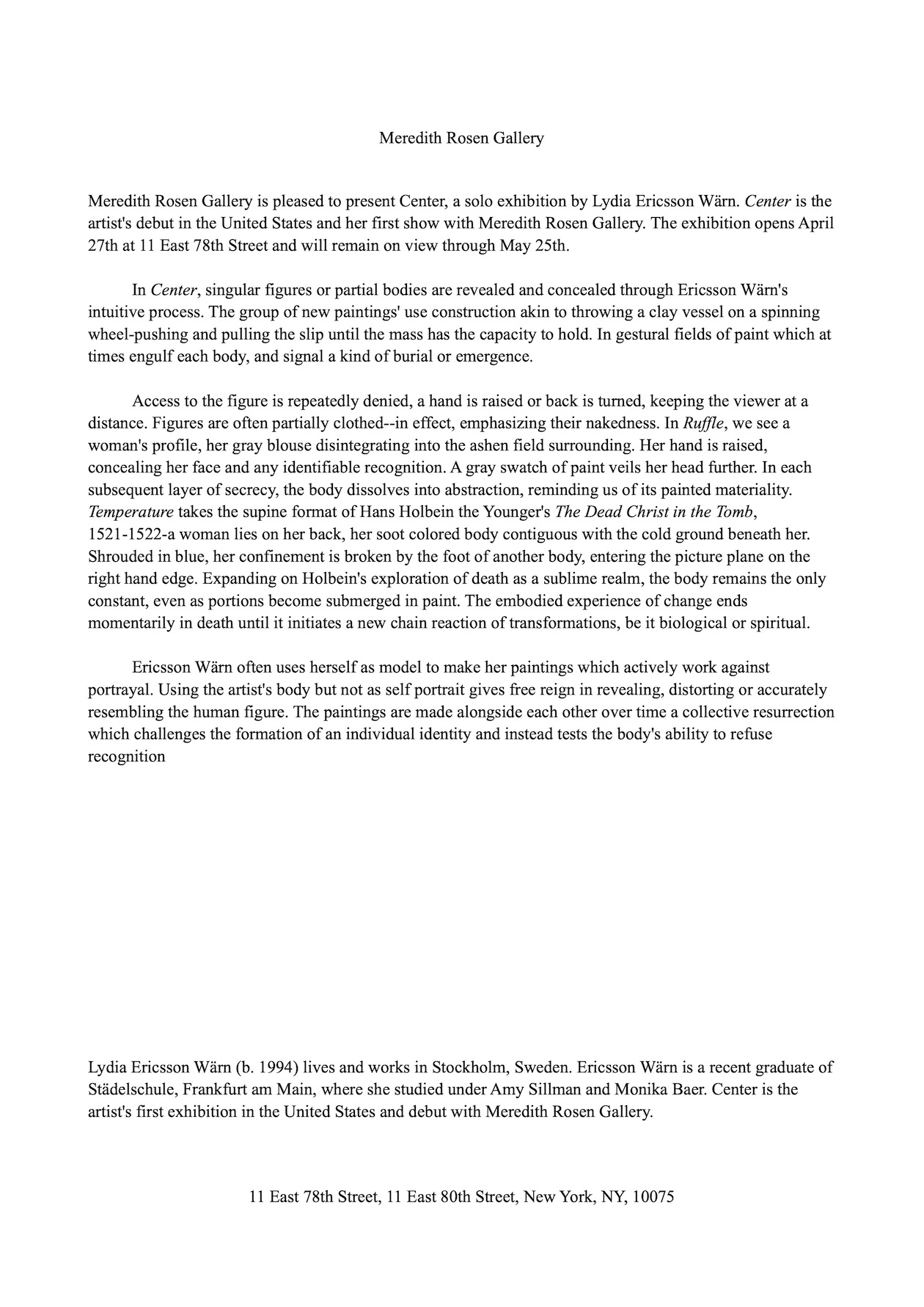

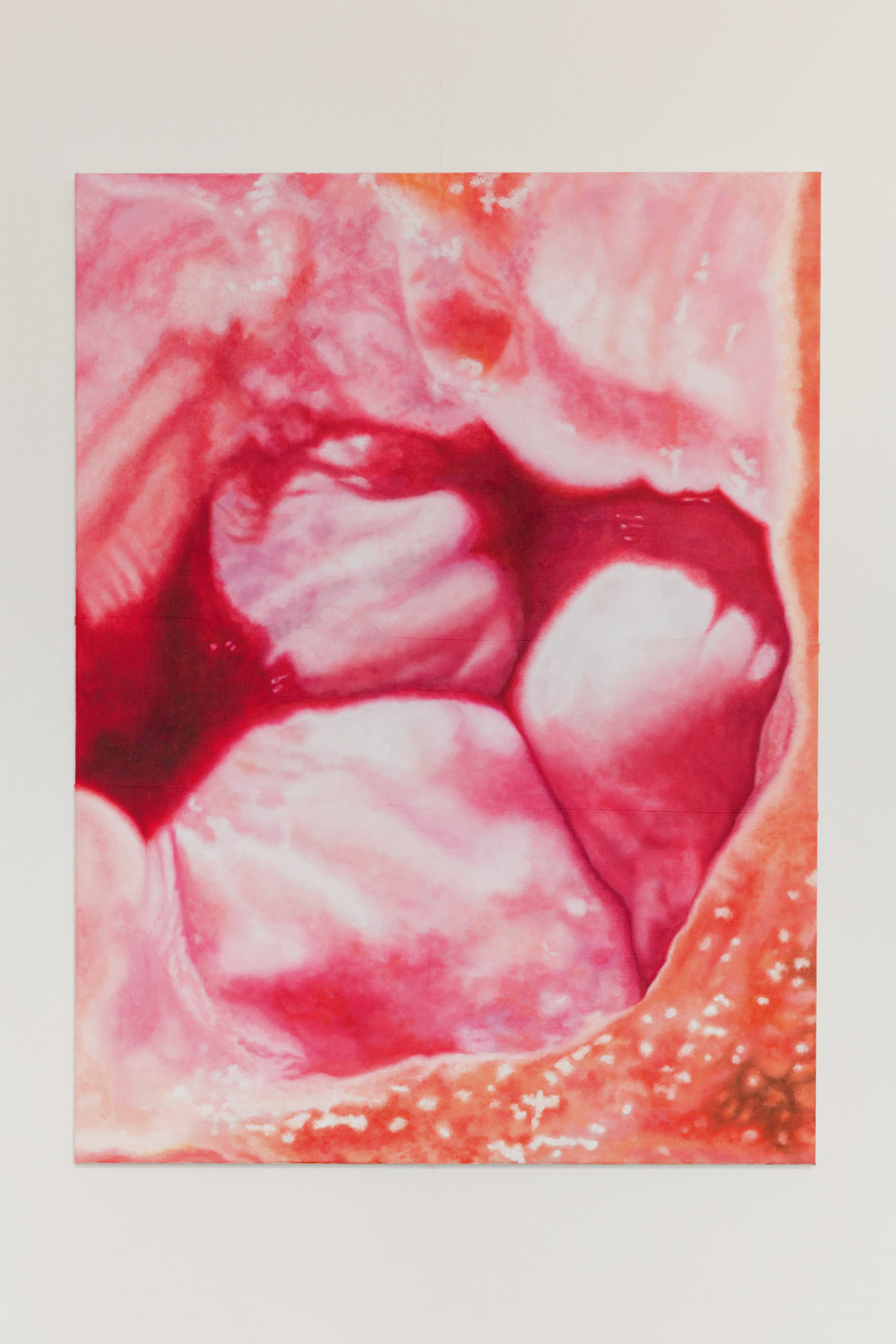

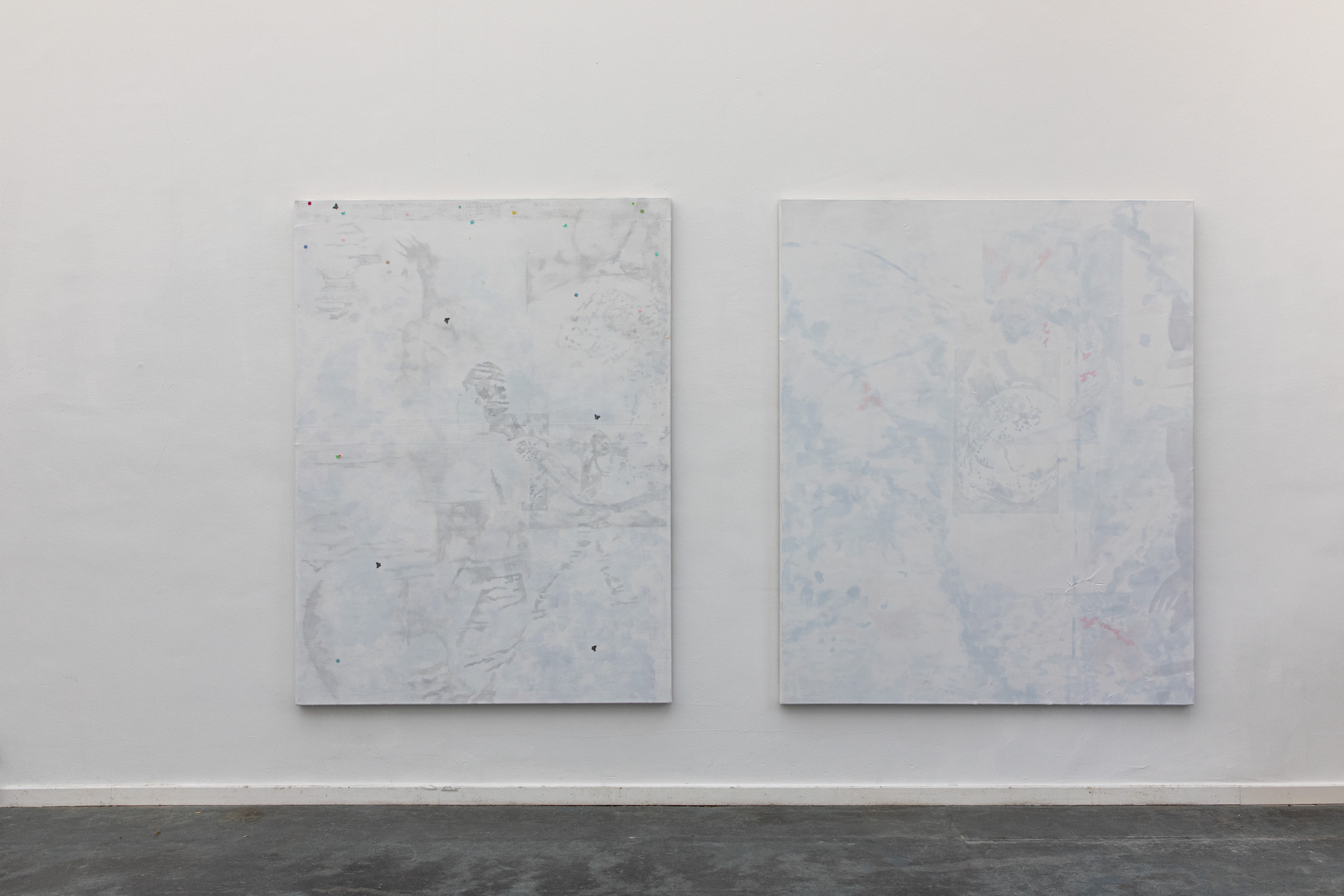

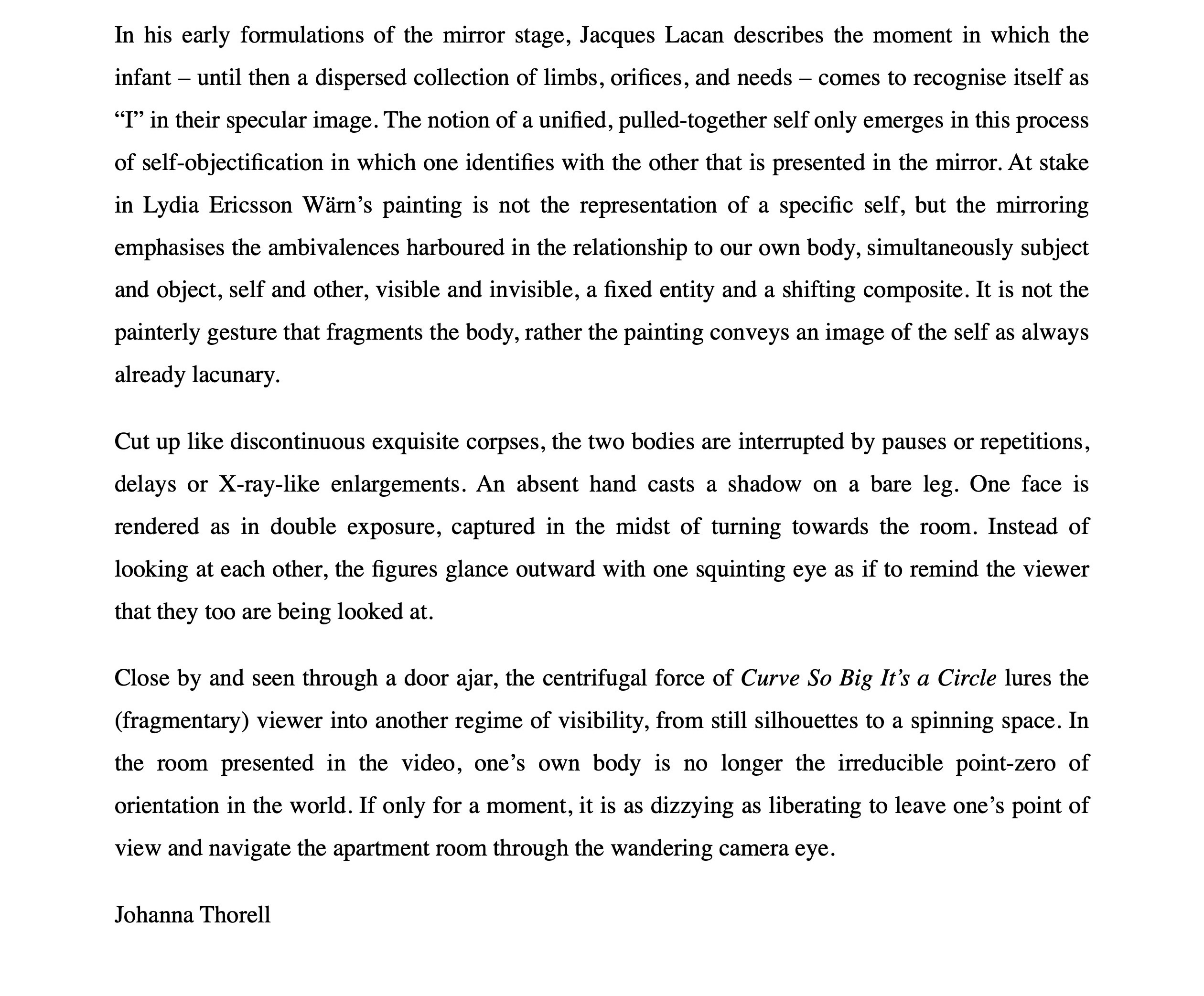

A painting in four parts, Phantasmatic Graft is a study of selfhood across a multiple body image. Separated by a foggy horizon or a turbid water surface that runs across the segmented picture plane, two full-length figures hover in front of each other. Like in a strangely altered mirror image, their faces and postures are almost identical, but their clothing and hand gestures differ. Same and other; a person's personas.

In his early formulations of the mirror stage, Jacques Lacan describes the moment in which the infant – until then a dispersed collection of limbs, orifices, and needs – comes to recognise itself as “I” in their specular image. The notion of a unified, pulled-together self only emerges in this process of self-objectification in which one identifies with the other that is presented in the mirror. At stake in Lydia Ericsson Wärn’s painting is not the representation of a specific self, but the mirroring emphasises the ambivalences harboured in the relationship to our own body, simultaneously subject and object, self and other, visible and invisible, a fixed entity and a shifting composite. It is not the painterly gesture that fragments the body, rather the painting conveys an image of the self as always already lacunary.

Cut up like discontinuous exquisite corpses, the two bodies are interrupted by pauses or repetitions, delays or X-ray-like enlargements. An absent hand casts a shadow on a bare leg. One face is rendered as in double exposure, captured in the midst of turning towards the room. Instead of looking at each other, the figures glance outward with one squinting eye as if to remind the viewer that they too are being looked at.

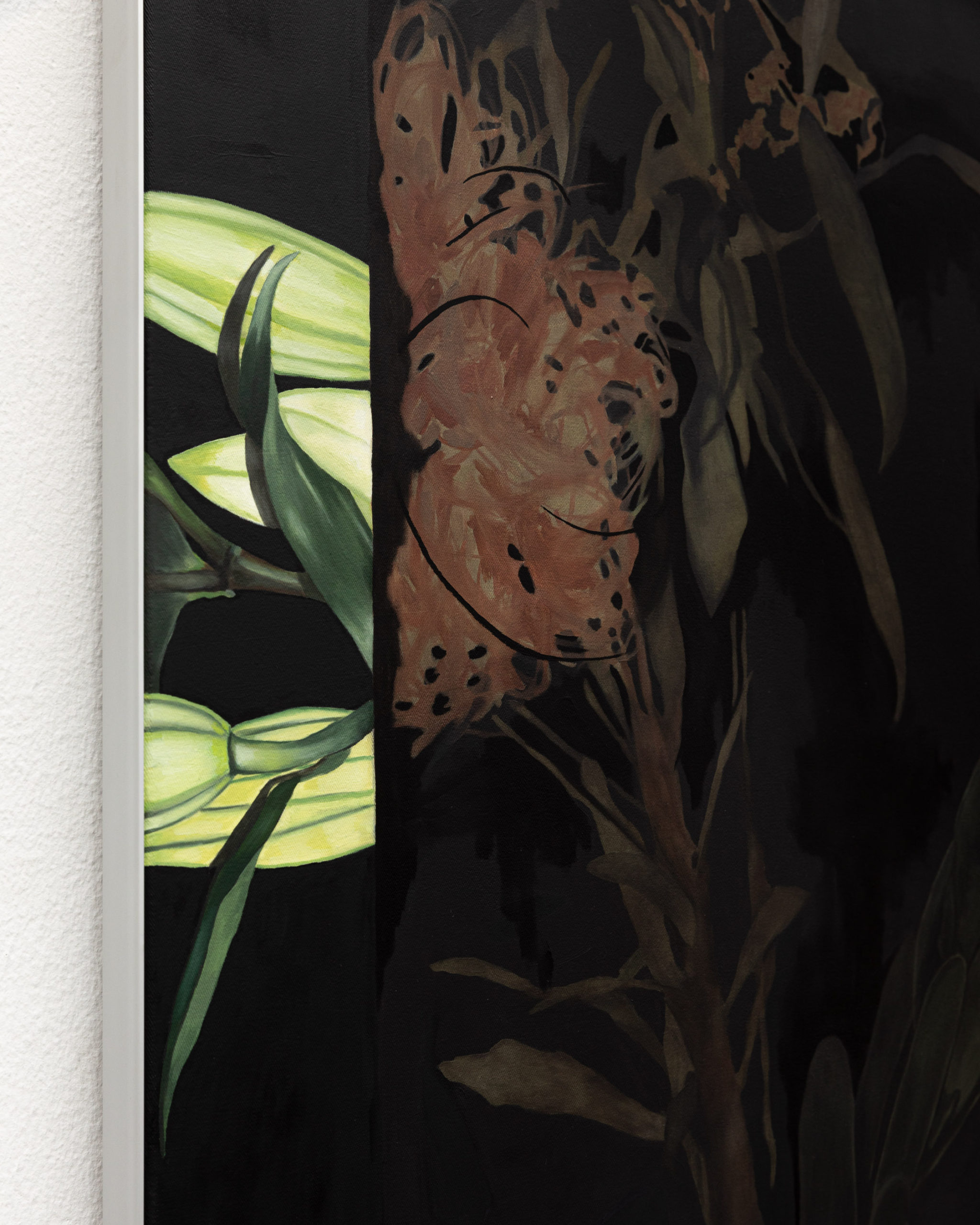

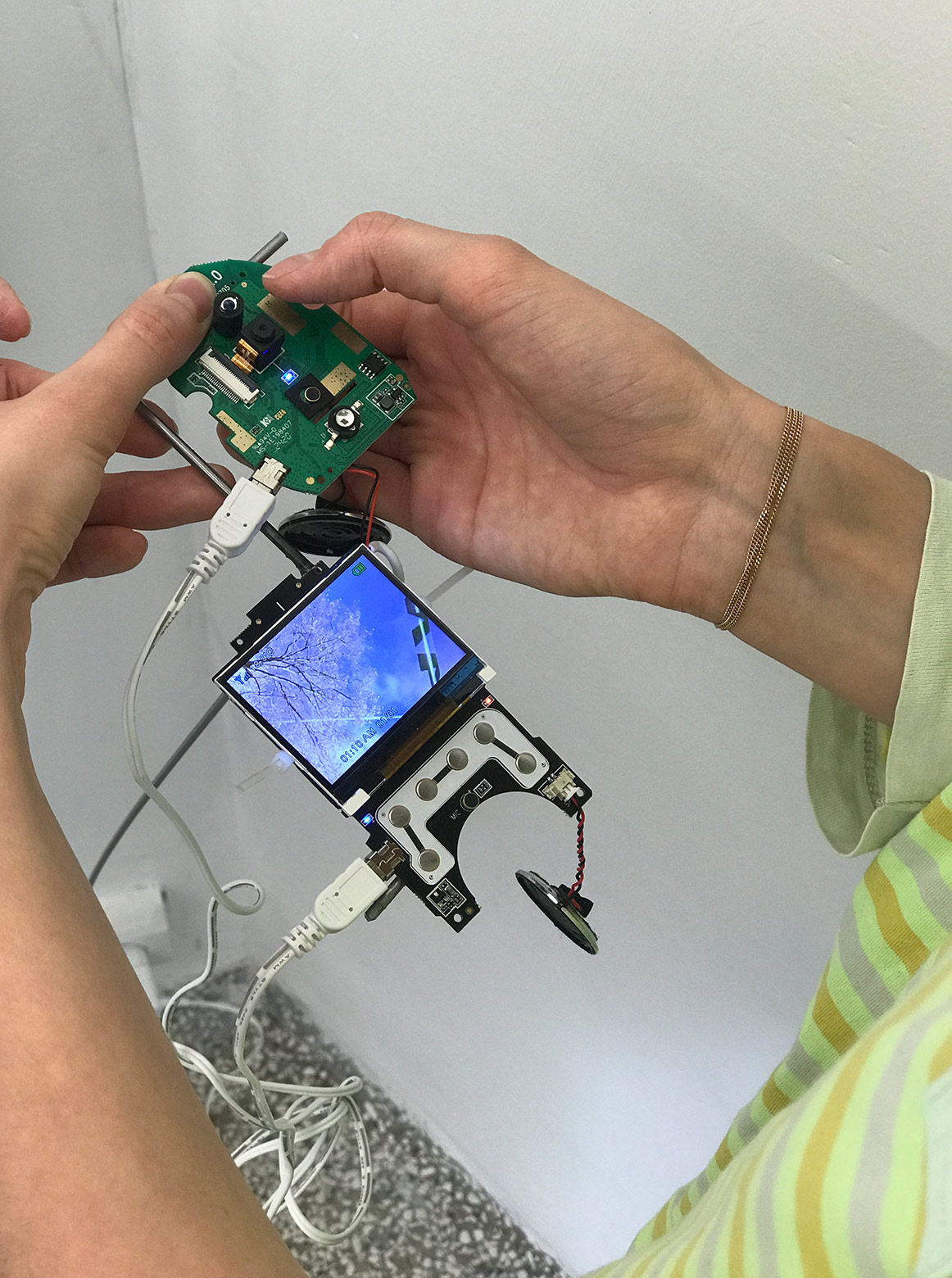

Close by and seen through a door ajar, the centrifugal force of Curve So Big It’s a Circle lures the (fragmentary) viewer into another regime of visibility, from still silhouettes to a spinning space. In the room presented in the video, one’s own body is no longer the irreducible point-zero of orientation in the world. If only for a moment, it is as dizzying as liberating to leave one’s point of view and navigate the apartment room through the wandering camera eye.

In his early formulations of the mirror stage, Jacques Lacan describes the moment in which the infant – until then a dispersed collection of limbs, orifices, and needs – comes to recognise itself as “I” in their specular image. The notion of a unified, pulled-together self only emerges in this process of self-objectification in which one identifies with the other that is presented in the mirror. At stake in Lydia Ericsson Wärn’s painting is not the representation of a specific self, but the mirroring emphasises the ambivalences harboured in the relationship to our own body, simultaneously subject and object, self and other, visible and invisible, a fixed entity and a shifting composite. It is not the painterly gesture that fragments the body, rather the painting conveys an image of the self as always already lacunary.

Cut up like discontinuous exquisite corpses, the two bodies are interrupted by pauses or repetitions, delays or X-ray-like enlargements. An absent hand casts a shadow on a bare leg. One face is rendered as in double exposure, captured in the midst of turning towards the room. Instead of looking at each other, the figures glance outward with one squinting eye as if to remind the viewer that they too are being looked at.

Close by and seen through a door ajar, the centrifugal force of Curve So Big It’s a Circle lures the (fragmentary) viewer into another regime of visibility, from still silhouettes to a spinning space. In the room presented in the video, one’s own body is no longer the irreducible point-zero of orientation in the world. If only for a moment, it is as dizzying as liberating to leave one’s point of view and navigate the apartment room through the wandering camera eye.

Johanna Thorell